CS149-Assignment3 A Simple CUDA Renderer

Contents

Part 1

The result is illustrated in the following figure.

Question 1

As you can see, due to the parallelism of the GPU, the bandwidth is huge.

Question 2

From the results, we can get that the bottleneck is the memory and CPU of the host itself. For the execution time of the kernel, the speed is very fast. However, the speed is low for copying the host memory into the device memory and vice versa.

Part 2

First, we need to implement the parallelism form of scan. The algorithm is super wonderful. You should first understand the algorithm.

1 | void exclusive_scan_iterative(int* start, int* end, int* output) { |

It may seem that we need N threads for every inner loop, however, this is a stupid idea, we should calculate how many threads we need for each inner loop.

Part 3

Before diving into how to write a render using CUDA. We first think about how to implement a render with cpp. And after that, you need to read the code written with CUDA.

First Implementation

For the first implementation, I focus on how to write the correct code. The hint part exclusive_scan has made me think we could first store the circle render parameters for each pixel. Thus we can scan the circle render parameters for each pixel.

Thus, we can solve the two important questions:

- Atomicity: we have made the memory independent for each pixel. So we can write whatever we want without any synchronization and mutation.

- Order: We have make an explicit array of render parameters. So the order doesn’t matter.

So, We first need to construct an array to hold the render parameters for each pixel.

1 | cudaMalloc(&cudaDevicePixelData, image->width * image->height * numCircles * 4 * sizeof(float)); |

Now, we first write the render information for every pixel. The core code is below:

1 | int pixelPtrStart = 4 * cuConstRendererParams.numCircles * (pixelY * imageWidth + pixelX) + 4 * circleIndex; |

Then we can launch a new kernel to calculate for each pixel:

1 | for (int i = 0; i < numCircles; ++i) { |

However, cudaDevicePixelData is too big, which will consume so much memory, which would exceed the maximum memory 16GB. So we need to reuse the render information. We should not store the information for every pixel. Because the render information of each circle is deterministic. But the things we need to make sure is that whether the circle has contributed to the pixel. So instead of storing the render information for each pixel, we could just use bit mask to indicate whether the circle has contributed to the pixel.

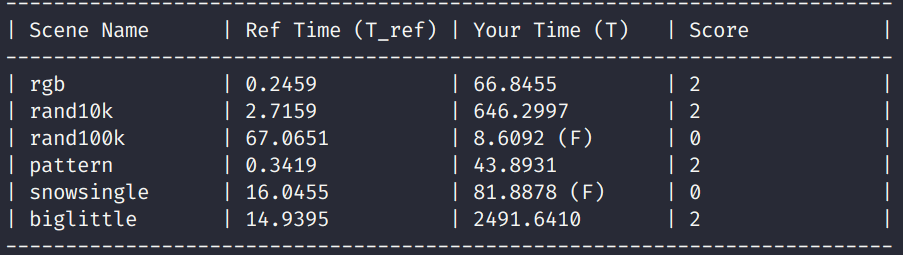

Now, the result is illustrated by below.

As you can see, we have passed some tests and the performance is not good at all. The reason why there are some failed tests is that the bytes exceed $2^{63}$, which would overflow.

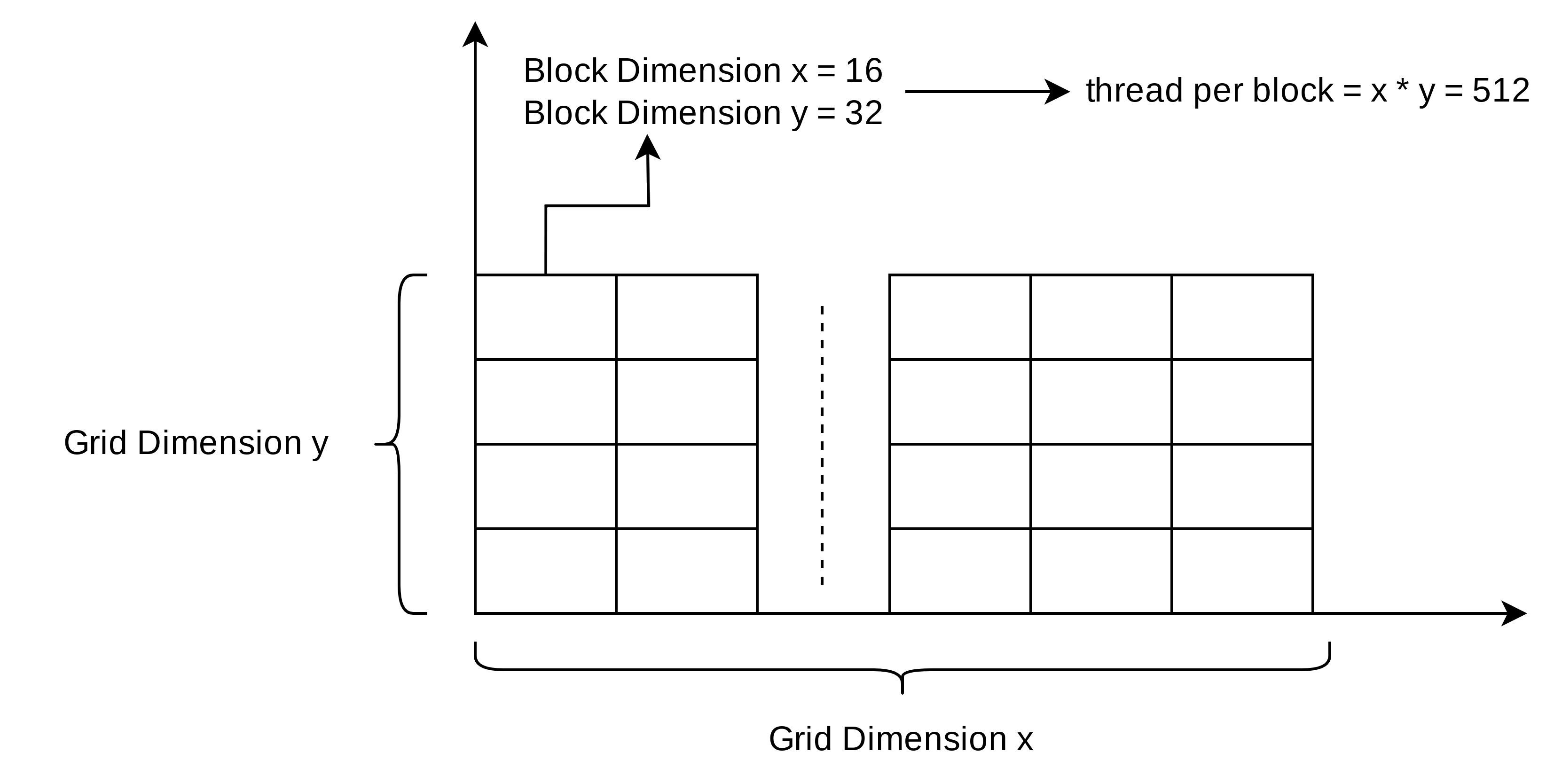

Best practice

We should use a clever way to solve this problem. The problem is a two-dimensional problem. So we’d better design the grid and block for two dimensions, as the following figures illustrates:

From the above figures, we could write the following code to initialize the grid and block size:

1 | void CudaRenderer::render() { |

And we should render a block each time, we have already split the pixels into the block. For each block, we should handle the each pixel, we could calculate the current pixel’s x coordinate and y coordinate and the current thread id:

1 | int thread_id = threadIdx.y * blockDim.x + threadId.x; |

So what a thread should do? We have already mapped a pixel $(x, y)$ with a specified thread. So the idea should be simple enough.

- We could traverse sequentially all the circles to tell whether the circle has contributed to this pixel, and we calculate to achieve rendering.

However, this way is too slow. For every pixel, we could calculate a lot of useless calculation. For example, if there are total 100,000,000 circles, there would be many useless circles for this pixel. So we should find a way to find the circles in the current block. So we could use a shared memory (a bit map) to know whether the BLOCK size circle has contributed to the block. So for each pixel (each thread) we could calculate ONLY one circle to know whether it has contributed to this block. And for each pixel, we could use the contributed circles to sequentially achieve rendering.

Look at what parallelism we have done:

- Each pixel renders itself using two-dimension task split.

- Each pixel handles 1 circle to tell whether it contributes to the current block for $num_{circles} / size_{block}$ loops.

It’s a really hard question, but it is very useful.

Author: shejialuo

Link: https://luolibrary.com/2023/06/07/CS149-Assignment3-A-Simple-CUDA-Renderer/

License: CC BY-NC 4.0